Microbes are tiny, and inviable in our naked eyes, yet they are everywhere. Microbes are providing ecosystem services for food production, environmental protection and human health. Some microbes, under certain conditions can also cause damages to humans, animals and plants, these are called pathogens.

An international group of scientists led by Prof Yong-Guan Zhu, from the Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences recently published a perspective in Science (15 September 2017), in which they discussed human impacts on this invisible microbial world, and how the microbial world responds to human impacts. For several billion years, microbes and the genes they carry have primarily been moved by physical forces such as air and water currents, and these forces have historically generated biogeographic patterns for microbes that are similar to those of animals and plants. Humans, particularly in the last 100 years, have significantly changed these dynamics. We perturb microbial populations by transporting large numbers of cells to new locations, and by modifying selection pressures at those locations. Through these processes, we are substantially altering microbial biogeography. Significant human perturbations include discharge of wastewater, manure and human transport.

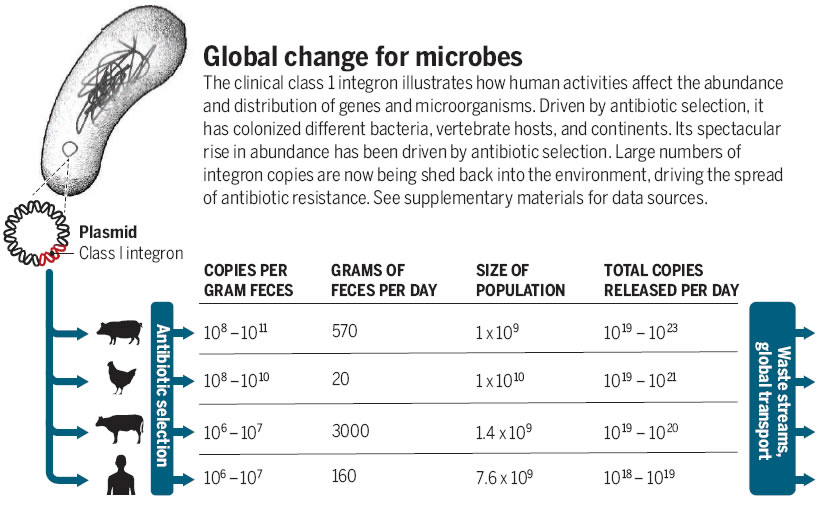

To illustrate this issue, the clinical class 1 integron is an excellent exapmle. This genetic element plays a central role in spreading antibiotic resistance genes between bacterial pathogens. DNA sequencing data shows that it had a single origin, in a single cell, sometime in the early 20th Century. Derivatives of this original element can now be found in diverse bacterial species, resident in many different vertebrate hosts, and on every continent. Millions to billions of copies of this element now occur in every gram of feces from humans and domestic animals. This spectacular increase in abundance and distribution has been driven by antibiotic selection, increases in population, and dissemination via global transport. The numbers of class 1 integrons released in waste streams mean that this DNA element has become a significant pollutant across wide geographic areas, with up to 1023 copies being shed into the environment every day.

Finally, they call for global research and monitoring of the microbial mass movements, and to investigate their consequences and mitigation strategies. They also propose a priority area, that is to fuse the conventional biogeochemical models with genomics datasets, so that we predict of the future changes of the microbial world in the Earth’s biosphere.