A group of international scientists have provided evidence that amoeba use arsenic to poison their bacterial prey (“Bacterial resistance to arsenic protects against protist killing”, Biometals, DOI 10.1007/s10534-017-0003-4). Protists were the first eukaryotes to evolve mainly using bacteria as their food source. Protists with an efficient mechanism to rapidly kill bacterial prey would have a selective advantage. Bacteria in turn would have to find mechanisms to protect themselves from protist grazing. How this relationship has evolved remains mysterious and our aim was to determine whether bacterial metal(loid) resistances play a role in protecting bacteria from metal(loid) poisoning in protists.

The team led by Christopher Rensing from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University in Fuzhou and Yong-Guan Zhu from the Institute of Urban Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiamen, China have shown that deletion of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) ars operon led to significantly lower intracellular survival in the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum (D. discoideum) compared to wild type E. coli. This suggests that protists use arsenic to poison bacterial cells in the phagosome, similar to their use of copper. In response to copper and arsenic poisoning by protists, there is a selection for acquisition of arsenic and copper resistance genes in the bacterial prey to avoid killing. In agreement with this hypothesis, both copper and arsenic resistance determinants are widespread in many bacterial taxa and environments, and they are often found together on plasmids. A role for heavy metals and arsenic in the ancient predator-prey relationship between protists and bacteria could explain the widespread presence of metal resistance determinants even in pristine environments.

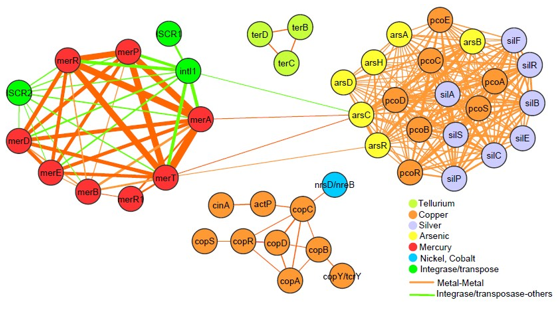

Co-occurrence of metal resistance genes on plasmids